The Impossibility of Writing — A Poetics

Writing is not, for me, a problem of lack, but of excess. As soon as I begin, no sentences appear, but fields. One formulation opens ten others, each with its own future, each reaching back into a different past. What presents itself is not a text but a moving network in which nothing ever comes to rest. Anyone who tries to choose within it is paralysed.

That is also why I often dictate (WhatsApp, etc.—to the frequent exasperation of my poor friends) instead of writing. Not because speaking is easier, but because writing asks for something else. Spoken language forces movement forward. It leaves less room for return. Less time to linger with what presents itself. Writing, by contrast, invites stillness, revision, reflection. And precisely there the problem begins.

Writing invites looking back.

I always look back.

That gesture is ancient. Orpheus descends to retrieve Eurydice. He is not allowed to see her before reaching daylight. Yet he turns around. Not out of weakness, but out of fidelity to what he truly wants: to see her as she is in the darkness itself. That is exactly where things go wrong. Whoever wants to make the invisible visible without betraying it loses it at the moment of beholding.

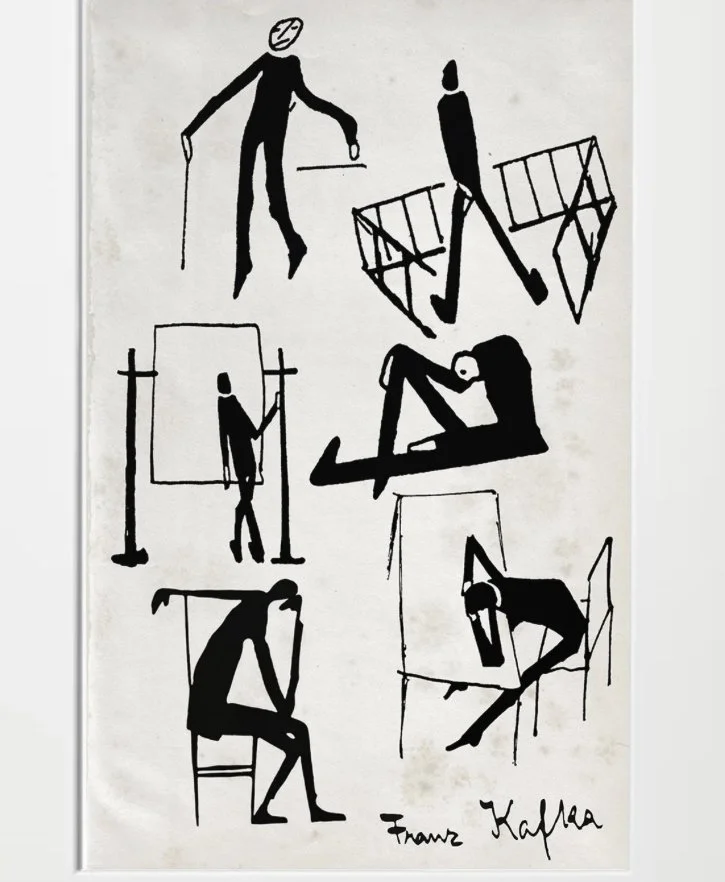

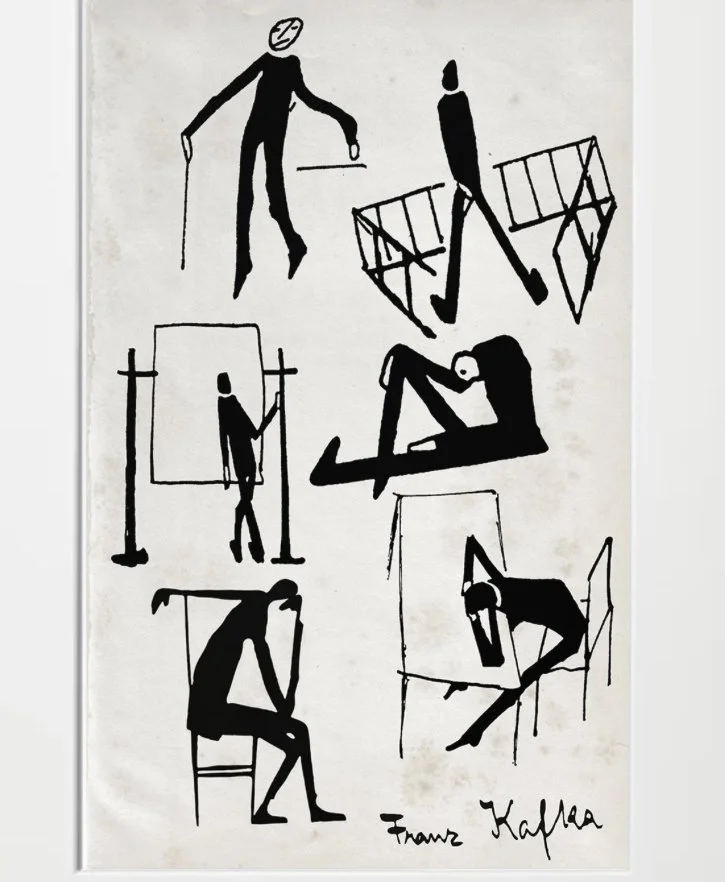

Kafka knew that this is not a mythical detail, but a structural law.

In The Bridge, the narrator is himself a bridge, stretched across an abyss. He knows he must not turn around. Yet he does, when he feels the footsteps of someone walking over him. At that moment he collapses. Not because he fails, but because he fulfils the logic of what he is.

The writer is such a bridge. Between an inner tension and a world that demands meaning. But a bridge exists only by grace of passage. As soon as someone steps onto it, the urge arises to look: who is reading me, what will this become for the other, how does this sound outside of me. That moment of reflexive attention is the moment at which the bridge loses its innocence.

For a long time I thought my struggle came from perfectionism. That I was searching for the right sentence and missing it by a hair each time. I now know this was a misunderstanding. The problem is not that the sentence remains imperfect. The problem is that I long for something that cannot, in principle, be fixed.

What I seek is coincidence. Words that do not refer, but coincide with what they carry. The sight of a playing child, a mother bent over a sleeping face, the accidental tenderness of a moment. I want such experiences to enter language without loss.

The accidental tenderness of a moment that presents itself without intention. From a certain mood, I already experience this as literature. Not as text, but as something that wants to speak.

That is not a writing mood. It is a mood of receptivity.

In such a mood, language seems to come of its own accord. The words appear to be already forming. Not literally, but as possibility, as promise. In that moment I do not experience myself as someone who makes something, but as someone through whom something moves. I would want to be a bridge, at that moment, between how I experience this and how another might experience it.

This becomes visible in an almost caricatural way in the familiar experience of the perfect letter that presents itself in half-sleep. Everything fits. The formulations seem exact. The tone is right. It feels as though the text already exists, as though it only still needs to be written down. But what is actually happening there?

It is not that those words are pure or private. A private language does not exist. These sentences, too, are fully publicly mediated. They are shaped by language, by others, by everything that has ever been read or heard. There is no untainted interior.

And yet there is a difference.

In that half-sleeping state I am not yet active. I write… barely. I find myself—or rather, I hover—in a mood in which meaning presents itself without responsibility. Without exposure. Social mediation is present, but it is, as it were, not yet being addressed.

But suppose a little demon were able to look over my shoulder at that moment and write down exactly what is being “written” in my head. Would it really turn out to be such a brilliant text? Or would it, once lifted out of that mood, lose its lustre entirely?

I am reminded of the anecdote about Paul McCartney who, during an LSD trip, urgently asks his friends to get pen and paper because he has an essential message. The next day he reads what was written down: there are seven levels. In the moment itself this was of overwhelming significance. Outside that state it proves empty.

This may teach us something fundamental. What appears there is not a hidden truth that only still needs to be recorded correctly. It is an experience that has meaning only within the mood in which it appears. Remove it from that context and it implodes. Like erotic arousal, which can fill everything with absolute intensity until it breaks and everything suddenly becomes meaningless.

That experience is not false. It is real. But it cannot be transmitted without losing itself.

And this does not apply only to half-sleep, trance, or intoxication. It applies to every mood of receptivity. At the moment I am moved by a scene—for example on a train, when I am touched by the face of a mother who, with a tender smile, passes her love on to her sleeping child—I already experience it as meaningful. But the moment I begin to write, I change position. I leave receptivity and enter activity. I now deliberately address another. I become a writer for a reader.

And precisely thereby I lose what I wanted to preserve.

Not because I do it badly, but because it cannot be otherwise.

The private exists only by grace of the public. It appears in the glow of possible shareability. But at the moment it truly has to be shared, it has already become something else. What remains is not an experience, but a trace. Not coincidence, but a distance made visible.

That is not a deficiency. It is the condition of literature.

Kafka called this the incapacity to write. At the same time, it was precisely the motor of his work. Not by chance could Kafka write only when he could momentarily pass beyond this insight, preferably at night, when the world fell silent, giving himself over to a rapture in which the old illusory promise could briefly flare up again. When writing was not a profession, but a break-in. Something that could exist only as long as it did not claim completion.

He distrusted endings. A finished text suggests that something has been found. That the gate has been passed, the promise fulfilled. For Kafka this was a form of betrayal. That is why his texts remained open, unfinished, abrasive. That is why he longed for the destruction of his work—not out of aversion, but out of fidelity to what writing truly was.

Writing can never be complete or pure expression. It remains postponement. A promise that sustains itself by not being fulfilled.

In that I recognise myself. On all levels. Because everything is a form of writing.

For a long time I believed there was a core within me, a true voice that merely needed to be struck correctly. That writing meant bringing that core outward. This turns out to be a spiritual illusion. What I call “inside” exists only thanks to distance. Without language, without form, without an outside world, there is no meaning—only intensity without direction.

The pain does not lie in failing to say something pure. The pain lies in the insight that purity itself is a mirage.

That does not make writing meaningless. It makes it precise. Writing is not an attempt to close, but to carry. Not a fixation of truth, but the keeping open of a space in which meaning can continue to move.

Kafka’s figures fail because they want to fix what can only circulate. They want to force access, dissolve guilt, stabilise meaning. They wait before gates meant only for them, and for that very reason never opening.

Writing means living with that gate.

Not forcing it. Not abandoning it. But remaining there. Continuing to write. Continuing to fail. Not seeing that failure as a deficiency, but as form.

Perhaps that is the only honest poetics. Writing as a bridge that collapses the moment it is truly crossed. Not because it is poorly built, but because it does exactly what it exists to do.

And perhaps that is also why I keep writing.

Not despite that collapse.

But because of it.

For readers interested in exploring this subject further, I would like to refer them to my book on Franz Kafka: ‘Into the White: Kafka and his metamorphoses’.